Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) is a severe violation of human rights and a significant global public health issue, with its widespread prevalence affecting communities worldwide. DV concepts are understood differently across various cultural, social, and legal contexts [1]. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition is one of the most recognized and globally accepted. WHO defines domestic violence as any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life [2]. On the other hand, the United Nations defines domestic violence or abuse as a pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner [3]. Both international organizations highlight that abuse might be physical, sexual, emotional, economic, or psychological actions or threats of actions that influence another person. The Republic of Moldova's legislation on preventing and combating domestic violence defines it as acts, including threats, of physical, sexual, psychological, spiritual, or economic violence (excluding self-defense actions) committed by a family member against another family member, inflicting material or moral damage upon the victim [4].

Although domestic violence has been recognized as a social problem for several decades, the extent of this phenomenon continues to have a significant prevalence today [5]. Domestic violence is considered an „unseen crime” that many victims may be too frightened or too ashamed to report [6]. It is therefore difficult, or even impossible, to produce accurate statistics on the true prevalence of this form of violence, as the number of reported instances will be much lower than the number of instances that actually occur [7]. However, globally, it is estimated that nearly one-third (30%) of women who have been in an intimate relationship have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence perpetrated by an intimate partner during their lifetime [2]. In some regions of the world, the percentages are even higher: 40.6% in Andean Latin America, 41.8% in West Sub-Saharan Africa, 41.7% in South Asia, and 65.6% in Central Sub-Saharan Africa [8]. According to WHO (2021), younger women are most vulnerable, 27% of women aged 15–49 worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence from their partner [9, 10]. Globally, 81,000 women and girls were killed in 2020, with around 47,000 of them (58%) dying at the hands of an intimate partner or family member, which equates to a woman or girl being killed every 11 minutes in their home [11, 12]. The Council of Europe reports that 45% of women have suffered from some form of violence during their lifetime, and between 12% and 15% of women in Europe over the age of 16 are victims of domestic violence [13]. In the Republic of Moldova, 73% of women have been subjected to at least one form of violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lives, physical violence being attested in 33% of cases, which is much higher than the average rate in the EU [14]. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Moldova, in 2022, 2,471 domestic violence cases were detected, with 81.3% of the victims being women [15]. We believe the dynamics of victims' reporting to the police can also reflect the extent of domestic violence. Thus, according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, there has been a constant increase in the reporting of cases, from 6,569 in 2012 to 15,526 in 2022. It is important to note that in the Republic of Moldova, domestic violence generates about 30 homicides and 5 cases of suicide annually [15].

Domestic violence significantly contributes to the ill health of society, and it is associated with many short- and long-term harmful physical and mental health problems and conditions [16, 17]. It is well known that the health sector plays a vital role in preventing domestic violence by helping to identify abuse early, providing victims with the necessary treatment, and referring them to appropriate care. Health services must be places where victims feel safe, are treated with respect, are not stigmatized, and can receive quality, informed support [18]. A comprehensive health sector response to the problem is needed, particularly in addressing the reluctance of victims to seek help [19]. For many victims, visiting a doctor is the first and often the only step toward accessing necessary medical care. Surveys indicate that women largely trust healthcare providers and consider it acceptable for doctors to ask about acts of violence if they suspect or find injuries on patients' bodies [20]. In this sense, medical professionals are uniquely positioned to intervene in critical situations for women and children who are constantly subjected to acts of violence [21]. The World Health Organization recommends training health practitioners to respond adequately to violence against women [16]. By providing safe and effective, victim-centered care, appropriately trained health practitioners can help alleviate the health consequences of violence and reduce its recurrence [22, 23]. These actions can have a significant impact on the health and well-being of DV victims, increase their access to high-quality, patient-tailored medical care, and ensure the protection of their rights [24].

Material and methods

An observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study based on a survey of medical students, residents, and doctors from Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy and medical institutions in the Republic of Moldova was conducted. In order to achieve the study's goal, a confidential questionnaire was designed, focusing on the following elements: the level of knowledge of medical students, resident doctors, and medical practitioners regarding domestic violence and specific elements of the health system's response to these cases, as well as their perceptions of social norms related to the roles of men and women in society and family. The questionnaire was developed in consultation with national partners, including representatives of civil society, specialized central public authorities responsible for preventing and combating domestic violence, and international institutions (World Health Organization, UN Women Moldova, UNFPA).

The questionnaire includes three sections: I) the respondent's demographic characteristics; II) an assessment of the respondent's knowledge in the field of domestic violence; III) an assessment of the respondents’ perceptions and attitudes toward domestic violence. It includes 49 questions, of which 43 are closed-ended, 3 are semi closed-ended, and 3 are open-ended, including scaled semantic and control questions. Some of the questions focused on identifying the respondent's opinion and its degree of expression using Likert scales (from 1 to 5).

As a general statistical community, 16,330 medical students and physicians were considered (4,116 students – Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy data, January 2023; 12,214 physicians – Statistical Yearbook "Public Health in Moldova 2022"). The representative sample was calculated in EpiInfo 7.2.2.6 program, „StatCalc – Sample Size and Power” section, based on the following parameters: a confidence interval for 95.0% significance of the results, a probability of the phenomenon's occurrence of 50.0%, and a design-effect of 2. Since the questionnaires were completed by respondents, to keep the sample representative, the probability of non-response was taken into consideration, which was predicted to be a maximum of 10.0% for the study sample. This resulted in an adjusted sample of 825 respondents, selected according to specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. The structure of the general statistical population was ensured by stratifying the sample according to the respondents’ professional status (students – 25.3%, residents/physicians – 74.7%). As a result, the final number of respondents in the representative sample should be at least: students – 209 and residents/physicians – 616.

To make it more convenient to survey respondents, the questionnaire was structured and administered on the Google Forms platform, ensuring unlimited access for potential respondents from across the country and from various specialties. The link to the questionnaire was distributed via email; its completion was voluntary and anonymous. Respondents' consent for completing the questionnaire was obtained. Microsoft Excel 2016 was used to collect the data, and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, ver. 26.0, was used for statistical analysis.

The study is part of the ”Medico-legal identification of adult victims of non-lethal physical domestic violence” research conducted at the Department of Forensic Medicine and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Minutes No. 3, May 18, 2023).

Results

I. The respondents' demographic characteristics

The questionnaire was completed by 832 respondents, of whom 214 (25.7%) were students, 96 (11.5%) were residents, and 522 (62.7%) were physicians. In terms of gender, females accounted for 78.2%, males 21.5%, and 0.2% of respondents identified as another gender. In this study, most participants were aged under 35 (386, 46.4%), being students or young professionals. Approximately 32.9% (274) of the total participants fell within the age range of 36-55 years, while only 172 (20.7%) were over 56 years old. Of the respondents, 82.0%studied or worked in rural medical institutions, and only 18.0% in urban ones. The study showed that most respondents had some professional experience: 28.1% had 21-40 years of professional experience, 24.5% had 6-20 years, 20.2% had less than five years, and 7.8% had more than 40 years. The study sample also included respondents with no work experience (19.4%).

An important aspect explored in the study was to find out how often respondents interacted with patients experiencing domestic violence. As a result, more than half of the respondents (64.4%) reported that they occasionally interact with patients who are victims of domestic violence, another 13.2% interact frequently, and only 1.4% interact daily. It is to be mentioned that 20.9% of respondents have never interacted with domestic violence victims during their professional lifetime, because most of them are students.

Within the survey, the respondents were asked to rate their level of knowledge regarding domestic violence and the health system's response to such cases on a scale of 1 to 5. The results revealed that 60.9% of the participants rated their level of knowledge as 1–3.

II. Assessment of the respondent's knowledge in the field of domestic violence

The aim of this section was to assess the level of knowledge and understanding of the domestic violence phenomenon and to identify possible gaps in this field. It consisted of 18 questions, both closed and open-ended, as well as a Likert scale, structured around the following topics: definition, causes and forms of domestic violence, role and response of the health system to such cases, and services available for victims of domestic violence.

Only 21.5% of respondents knew that domestic violence is a crime and a violation of human rights due to the imbalance of power. This fact highlights the limited knowledge of the respondents and the presence of misconceptions about domestic violence. The study also reveals that the most recognized form of domestic violence is physical (in 95% of responses), followed by psychological (39.1%) and sexual violence (25.3%). It should be noted that 63.9% of respondents demonstrated the ability to recognize vulnerable categories of people subject to domestic violence.

An important aspect of the study was to assess medical practitioners' understanding of the health system's role in addressing domestic violence. The study findings highlighted that a notable proportion of respondents (34.9%) believe that the role of the health system in combating domestic violence is insignificant. On the other hand, it is encouraging to find that 70.9% of respondents (with a mean score of 3.8) agreed that a physician's inability to recognize victims of domestic violence affects the quality of medical care provided, thus acknowledging the major role they play in identifying and appropriately handling such cases. Regretfully, more than half of the respondents (61.3%) believe that documentation of injuries is an exclusive task of the forensic doctor (Table 1). This misconception affects the provision of evidence for the judicial act.

Table 1. Respondents' opinions on the role of the health system in addressing domestic violence | ||||||

Statement | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Mean score |

The role of the health system in combating domestic violence is insignificant | 82 (9.9%, 95% CI 7.9–12.0) | 208 (25.0%, 95% CI 22.0–28.0) | 116 (13.9%, 95% CI 11.7-16.1) | 171 (20.6%, 95% CI 17.9–26.6) | 255 (30.6%, 95% CI 27.6–34.0) | 2.7 |

Physicians' inability to identify victims of domestic violence affects the quality of medical care provided to them | 285 (34.3%, 95% CI 31.1–37.7) | 306 (36.8%, 95% CI 33.2–40.1) | 97 (11.7%, 95% CI 9.4–13.9) | 75 (9.0%, 95% CI 7.1–11.2) | 69 (8.3%, 95% CI 6.4–10.3) | 3.8 |

Medical care for victims of domestic violence can be affected by the doctor's misconceptions in this regard | 156 (18.8%, 95% CI 16.2–21.3) | 281 (33.8%, 95% CI 30.5–37.0) | 202 (24.3%, 95% CI 21.5–27.2) | 95 (11.4%, 95% CI 9.4–13.6) | 98 (11.8%, 95% CI 9.6–13.9) | 3.3 |

Documentation of injuries is an exclusive task of the forensic doctor | 300 (36.1%, 95% CI 32.9–39.5) | 210 (25.2%, 95% CI 22.4–28.0) | 122 (14.7%, 95% CI 12.3–17.2) | 90 (10.8%, 95% CI 8.5–13.0) | 110 (13.2%, 95% CI 10.8–15.6) | 3.4 |

Note: Respondents' opinions on the role of the health system in addressing domestic violence are presented. Each statement is rated on a Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). The table shows the distribution of responses and includes the mean score for each statement. | ||||||

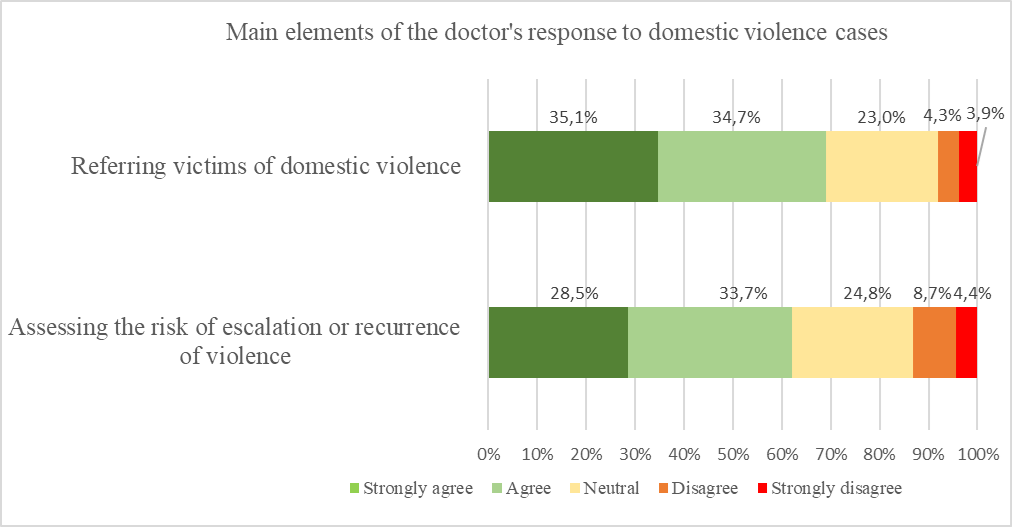

To assess healthcare providers' awareness of their role in addressing domestic violence, the authors asked respondents for their opinions on two important elements of the doctor's response to domestic violence cases. Responses revealed (Figure 1) that 69.8% of respondents agreed that referring victims of domestic violence is part of the doctor's response to domestic violence cases, as well as assessing the risk of violence escalation or recurrence (62.2%).

|

Fig. 1 Respondents' opinions on statements regarding their role in managing domestic violence cases *The opinions of healthcare providers regarding two key aspects of managing domestic violence cases are presented. Each statement is rated by healthcare providers on a Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). The figure likely illustrates the distribution of responses for both statements. |

Additionally, the study investigated respondents' awareness of the barriers that prevent women survivors of domestic violence from accessing healthcare services and disclosing abuse to medical staff. Through an open-ended question, participants identified barriers such as fear, shame, stigma, lack of information, distrust in the healthcare system, financial dependence on the abuser, and unawareness of their rights. Furthermore, as an important barrier, 52.6% of respondents identified doctors' misconceptions in the field of domestic violence as a factor that could prevent victims from accessing quality healthcare services (Table 1). It is encouraging that doctors are aware of the real barriers also described in the literature, as this would help them to anticipate and manage them appropriately, thus supporting victims to disclose cases of domestic violence in order to provide an effective and non-discriminatory response

The survey also included questions aimed at assessing respondents' knowledge regarding legal protection measures for victims of domestic violence. As a result, 89.1% of the participants did not know the legal protection measures. Thus, 88.5% of them wrongly consider that informing the social worker and/or the local mayor is an instrument of legal protection, and 11.5% believe that in the Republic of Moldova, there are no legal instruments for the protection of domestic violence victims. In terms of reporting to the police, only 33.8% of respondents knew that physicians have the duty to inform the police without the children's consent, and the adult victim's consent when a danger to her life and health is present. It's notable that 81.5% of respondents know that in the Republic of Moldova, there are support services for victims of domestic violence.

III. Assessment of respondents' perceptions and attitudes towards domestic violence

The third section was designed to assess respondents' perceptions and attitudes towards domestic violence and to identify misconceptions regarding this topic. It includes 16 closed-ended questions addressing how participants perceive the phenomenon of domestic violence, including opinions and personal experiences. The majority of the questions are Likert-scaled statements. Due to space constraints, this paper presents the analysis of only 6 questions. Table 2 illustrates five of the most widely believed and deep-rooted misconceptions in society and the respondents' opinions.

Table 2. Respondents' opinions on statements regarding their perceptions and attitudes toward DV | ||||||

Statement | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Mean score |

Domestic violence is a public health problem | 512 (61.5%, 95% CI 58.4–65.1) | 164 (19.7%, 95% CI 17.1–22.2) | 92 (11.1%, 95% CI 8.9–13.2) | 36 (4.3%, 95% CI 3.0–5.8) | 28 (3.4%, 95% CI 2.2–4.8) | 3.8 |

Domestic violence is a private issue | 23 (2.8%, 95% CI 1.8–4.0) | 58 (7.0%, 95% CI 5.4–8.7) | 122 (14.7%, 95% CI 12.4–17.1) | 133 (16.0%, 95% CI 13.5–18.4) | 496 (59.6%, 95% CI 56.5–63.0) | 2.3 |

Domestic violence occurs only in poor families | 27 (3.2%, 95% CI 2.0–4.6) | 160 (19.2%, 95% CI 16.7–21.9) | 115 (13.8%, 95% CI 11.4–16.1) | 182 (21,.9%, 95% CI 19.1–24.8) | 348 (41.8%, 95% CI 38.7–45.1) | 2.7 |

There are times when a woman deserves to be hit by her life partner | 20 (2.4%, 95% CI 1.4–3.4) | 25 (3.0%, 95% CI 1.9–4.2) | 50 (6.0%, 95% CI 4.4–7.6) | 52 (6.3%, 95% CI 4.7–8.1) | 685 (82.3%, 95% CI 79.7–84.9) | 2.1 |

Alcohol consumption is the cause of domestic violence | 501 (60.2%, 95% CI 57.0–63.7) | 209 (25.1%, 95% CI 22.0–28.0) | 43 (5.2%, 95% CI 3.7–6.9) | 33 (4.0%, 95% CI 2.8–5.5) | 46 (5.5%, 95% CI 4.0–7.2) | 3.9 |

Note: Respondents' opinions on various statements regarding their perceptions and attitudes toward domestic violence are presented. Each statement is rated on a Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). The table displays the distribution of responses. Additionally, the table includes the mean score for each statement, providing a summary measure of the overall trend in respondents' attitudes and perceptions. | ||||||

The results revealed that 81.2% of participants consider domestic violence a public health problem, and 85.6% of them vehemently disagree that domestic violence is a private issue. Moreover, 91.9% of the participants demonstrated their position against this phenomenon by firmly stating that domestic violence is unacceptable under any circumstances. A higher proportion of the participants (88.6%) strongly disapprove of the idea that women sometimes deserve to be hit by their life partner.

However, 22.4% of respondents believe that domestic violence occurs only in poor families, and almost all the participants (85.3%) think that alcohol consumption is the cause of domestic violence.

Participants also strongly disagree (88.6%) that sometimes a woman deserves to be hit by her life partner, which demonstrates again that they are familiar with the physical form of domestic violence.

The authors note that there were no statistically significant differences in the responses to all the aforementioned statements and questions based on the respondents' essential characteristics, including gender, age, marital status, and work status.

Discussion

The essential point in selecting the sample was that domestic violence is a public health problem, and it is crucial for doctors to have specific knowledge and skills to ensure an adequate response and prevention of the phenomenon. The authors noted that 85.7% of the respondents in this survey shared the same opinion. Moreover, 88.7% of them confirmed this by stating that the main reason for attending future training in this field is that they are aware of the problem and want to be informed.

The present study highlights the need for improvement in respondents' knowledge and attitudes towards violence. The answers to the second part of the questionnaire, which targeted elementary knowledge about the general concept and role of the health system in addressing cases of domestic violence, showed that respondents are not fully aware of what the concept of domestic violence is and what forms it can take. This knowledge is fundamental for providing effective support and assistance to victims of domestic violence and can significantly affect the health and well-being of DV victims.

This observation is also demonstrated by the fact that even the participants recognized themselves as possessing an insufficient level of knowledge, with more than half rating it as medium or lower. We strongly believe that this can be explained by the fact that 60.8% of respondents had not previously received training in this area, which likely influenced their self-assessment of knowledge. It is remarkable that 70.0% of respondents are aware of their own deficiencies in understanding how they should react in such cases and are interested in attending training in this field. 88.7% of them said that one of the reasons they would attend training again is that they are aware of the problem and want to be informed.

Only 21.5% of participants were aware of the definition of domestic violence, but only a limited number (around 1%) of them were able to state all forms of domestic violence. The most recognized was physical violence, despite Law No. 45/2007 on preventing and combating domestic violence stipulating five forms of domestic violence: physical, sexual, psychological, spiritual, and economic [4].

In our study, we found that the least recognized forms of domestic violence were spiritual and economic ones. We consider that limited awareness of healthcare providers about all forms of domestic violence can lead to overlooked cases and inadequate responses, as well as restricting the victims' access to high-quality and need-tailored healthcare services.

It is important to underline that 34.9% of the participants think the role of the health system in combating domestic violence is insignificant. This observation leads us to believe that they are not fully aware of the contribution they have made in addressing this important problem. The existence of such an opinion among more than a third of medical professionals is quite worrying, as it contradicts the general conception of the importance of the medical system in dealing with domestic violence. Thus, underestimating this role could lead to inadequate provision of assistance to victims of domestic violence and undermine efforts to prevent this serious phenomenon. However, more than half of respondents recognized referring DV victims and assessing the violence escalation risk as elements of the physicians' response to domestic violence. This suggests that participants are still aware that they are playing a significant role in addressing this issue, but not in a good enough manner.

To ensure the victim's safety and protection, health workers must inform the victim about existing legal protection measures. Unfortunately, our study revealed that current and future physicians do not know them, which can affect the victims' ability to ask for these measures. According to Moldovan legislation [4, 21], healthcare providers must report DV cases to the police when children are involved and a danger to an adult victim's life or health is present without their consent. Regrettably, only a third of respondents knew about this duty. This gap can lead to a late start of a criminal case and increase risks of violence recurrence.

Healthcare providers, like many other members of society, can be affected by misconceptions and stereotypes about domestic violence and women subjected to violence. Misconceptions and stereotypes associated with domestic violence may influence how health professionals understand and respond to cases of domestic violence in their professional practice. For appropriate and effective intervention, healthcare professionals must distinguish between myths and the reality that underlies the phenomenon of domestic violence. To assess respondents' perceptions and attitudes towards the phenomenon of domestic violence, the authors used a series of well-known myths to find out the participants' opinions. Myths are ideas and beliefs that have no objective foundation and are not based on facts. These misconceptions disseminate incorrect information about the phenomenon and its origins, influencing how it is perceived and how society reacts to cases of violence [20].

The study revealed that domestic violence is seen by doctors as a public health problem and not as a private issue. Despite respondents' belief that there are no circumstances which would excuse the application of force against a woman, they are still affected by some myths. Thus, they wrongly think that DV occurs only in poor families and alcohol consumption is its cause. It is well known that myths are harmful, as they distort the actual situation of domestic and gender-based violence, and due to this fact, they can discourage healthcare professionals' intervention [20].

Conclusions

The study revealed that current and future doctors strongly need to be trained in order to strengthen their capacity to adequately respond to cases of domestic violence. Analysis of perceptions showed that medical respondents are still affected by some stereotypes, as other members of society, but to a lesser extent. The National Strategy on preventing and combating domestic violence stipulates the compulsory nature of both primary and continuous education for medical staff in the field of domestic violence. The results of this study provide an overview of current and future physicians' knowledge and approaches and may be used as evidence-based proposals for enriching existing training programs or designing new ones, in order to support healthcare practitioners in the proper management of domestic violence cases. Proper knowledge and attitudes are essential to ensure respect for human rights and the effective implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (2011) in the Republic of Moldova.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

AP conceived the study, contributed to its design, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. PG and AB designed the questionnaire, collected the data, and conducted its analysis. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements and funding

The study received no external funding.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Minutes 3 from May 18, 2023).

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Authors' ORCID IDs

Petru Glavan – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9128-3864

Andrei Pădure – https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4249-9172

Anatolii Bondarev – https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1861-7490

References

Rollè L, Ramon S, Brustia P. New perspectives on domestic violence: from research to intervention. Front Psychol. 2019;10:641. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00641.

- World Health Organization. Violence against women [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

- United Nations. What is domestic abuse? [Internet]. Geneva: UN; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse

- Republica Moldova, Parlamentul. [Republic of Moldova, The Parliament]. Legea nr. 45 din 01.03.2007 cu privire la prevenirea şi combaterea violenţei în familie [Law No. 45 of 01.03.2007 on preventing and combating domestic violence]. Monitorul Oficial al Republicii Moldova. 2008;(55-56): art. 178. Romanian.

- Guvernul Republicii Moldova [Government of the Republic of Moldova]. Hotărârea nr. 281/2018 cu privire la aprobarea Strategiei naţionale de prevenire și combatere a violenţei faţă de femei și a violenţei în familie pe anii 2018-2023 și a Planului de acţiuni pentru anii 2018-2020 privind implementarea acesteia [Decision No. 281/2018 on the approval of the National Strategy for Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence for the years 2018-2023 and the Action Plan for the years 2018-2020 regarding its implementation]. Monitorul Oficial al Republicii Moldova. 2018;(121-125). Romanian.

- Gîngota E, Spinei L, Calac M, Potîng L. Aspecte sociale, medicale și legale în prevenirea și combaterea violenței în perioada pandemiei COVID-19 [Social, medical and legal aspects in prevention and controlling violence during COVID-19 pandemic]. Sănătate Publică, Economie şi Management în Medicină. 2020; 3 (85): 7-14. Romanian.

- McQuigg RJA. The Istanbul Convention, domestic violence and human rights. Abingdon; New York: Routledge; 2017. 183 p.

- Renzetti CM, Follingstad DR, Coker L, editors. Preventing intimate partner violence: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Bristol: Policy Press; 2017.

- World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2024 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256

- Hollingdrake O, Saadi N, Alban Cruz A, Currie J. Qualitative study of the perspectives of women with lived experience of domestic and family violence on accessing healthcare. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(4):1353-1366. doi: 10.1111/jan.15316.

- UN Women. Facts and figures: Ending violence against women [Internet]. New York: UN Women; 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Killings of women and girls by their intimate partner or other family members Global estimates 2020 [Internet]. Vienna: UNODC; 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/UN_B…

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul, 11.05.2011) [Internet]. Strasbourg: CE; 2011 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://rm.coe.int/168008482e

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevanlence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2013 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625

- Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Moldova. Notă informativă privind starea infracţionalităţii ce atentează la viaţa şi sănătatea persoanei şi celor comise în sfera relaţiilor familiale pe parcursul a 12 luni ale anului 2022 [Informative note regarding the state of crime that threatens the life and health of the person and those committed in the sphere of family relations during the 12th month of 2022] [Internet]. Chisinau: The Ministry; 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://politia.md/sites/default/files/nota_informativa_privind_violenta_in_familie_12_luni_2022_0.pdf. Romanian.

- World Health Organization. Addressing violence against women in pre-service health training: integrating content from the Caring for women subjected to violence curriculum. Geneva: WHO; 2022. 54 p.

- Glavan P, Padure A, Bondarev A. Impactul violenței în familie asupra victimelor și comunității [Domestic violence’s impact on victims and communities]. Arta Medica. 2024;(4):23-27. Romanian.

- Morari G, Pădure A, Zarbailov N. Ghid pentru specialiștii din sistemul de sănătate privind intervenția eficientă în cazurile de violență împotriva femeilor [Guide for healthcare professionals on effective intervention in cases of violence against women]. Chișinău: Cartea Juridică; 2016. 160 p. Romanian.

- World Health Organization; García-Moreno C, et al. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva: WHO; 2005. 206 p.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against women: an EU-wide survey Main results. Luxembourg: EUAFR; 2015. 193 p.

- Pădure A, Țurcan-Donțu A. Domestic and gender-based violence: (Training manual). Chişinău: [s. n.]; 2022. 176 p.

- Guvernul Republicii Moldova [Government of the Republic of Moldova]. Hotărârea nr. 270/2014 cu privire la aprobarea Instrucţiunilor privind mecanismul intersectorial de cooperare pentru identificarea, evaluarea, referirea, asistenţa şi monitorizarea copiilor victime şi potenţiale victime ale violenţei, neglijării, exploatării şi traficului [Decision No. 270/2014 on the approval of the Instructions on the intersectoral cooperation mechanism for the identification, assessment, referral, assistance and monitoring of child victims and potential victims of violence, neglect, exploitation and trafficking]. Monitorul Oficial al Republicii Moldova. 2014;(92-98). Romanian.

- Toporeț N, Pădure A, Bondarev A, Glavan P. Role of the health system and forensic medical investigations in proving domestic violence. Rom J Legal Med. 2022;(3):200-203. doi: 10.4323/rjlm.2022.200.

- Pădure A, Glavan P, Bondarev A, Spinei L, Cazacu D. Cunoştinţele şi percepţiile medicilor şi mediciniştilor cu privire la violenţa in familie [Knowledge and perceptions of doctors and medical students regarding domestic violence]. Chişinău: 2023 (Print-Caro). 116 p. ISBN 978-9975-180-09-2. Romanian.